What You Need To Know About the Recent Measles Outbreak

Free Special Topics: Measles Module. Check your Rosh Review Boost Box for a free review of what you need to know about measles. Get your free access.

Check your Rosh Review Boost Box for a free review of what you need to know about measles. Get your free access.

All info below is from the CDC website

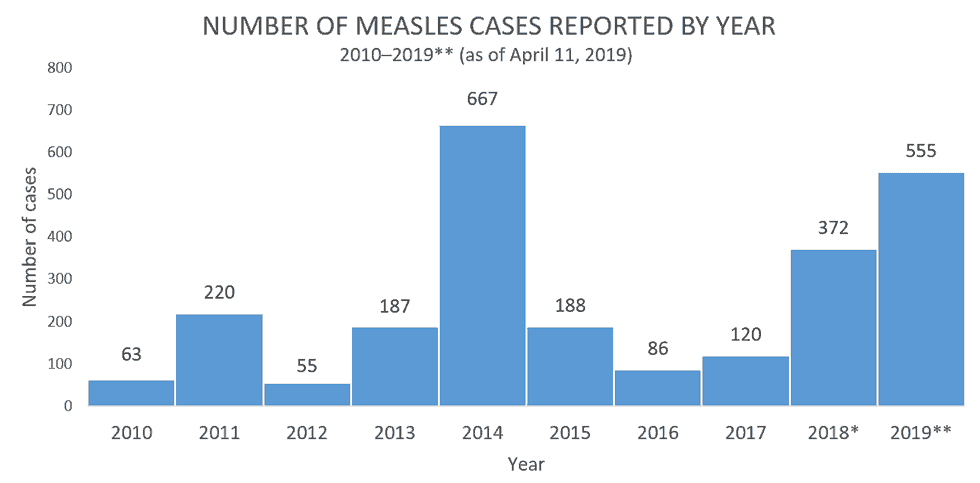

From January 1 to April 11, 2019, 555 individual cases of measles have been confirmed in 20 states. This is the second-greatest number of cases reported in the U.S. since measles was eliminated in 2000.

The states that have reported cases to CDC are Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Texas, and Washington.

Complications

Common complications from measles include otitis media, bronchopneumonia, laryngotracheobronchitis, and diarrhea.

Even in previously healthy children, measles can cause serious illness requiring hospitalization.

- One out of every 1,000 measles cases will develop acute encephalitis, which often results in permanent brain damage.

- One or two out of every 1,000 children who become infected with measles will die from respiratory and neurologic complications.

- Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a rare, but fatal degenerative disease of the central nervous system characterized by behavioral and intellectual deterioration and seizures that generally develop 7 to 10 years after measles infection.

People at High Risk for Complications

People at high risk for severe illness and complications from measles include:

- Infants and children aged <5 years

- Adults aged >20 years

- Pregnant women

- People with compromised immune systems, such as from leukemia and HIV infection

Transmission

Measles is one of the most contagious of all infectious diseases; up to 9 out of 10 susceptible persons with close contact to a measles patient will develop measles. The virus is transmitted by direct contact with infectious droplets or by airborne spread when an infected person breathes, coughs, or sneezes. Measles virus can remain infectious in the air for up to two hours after an infected person leaves an area.

Vaccination

Measles can be prevented with measles-containing vaccine, which is primarily administered as the combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. The combination measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine can be used for children aged 12 months through 12 years for protection against measles, mumps, rubella and varicella. Single-antigen measles vaccine is not available.

One dose of MMR vaccine is approximately 93% effective at preventing measles; two doses are approximately 97% effective. Almost everyone who does not respond to the measles component of the first dose of MMR vaccine at age 12 months or older will respond to the second dose. Therefore, the second dose of MMR is administered to address primary vaccine failure.

Vaccine Recommendations

Children

CDC recommends routine childhood immunization for MMR vaccine starting with the first dose at 12 through 15 months of age, and the second dose at 4 through 6 years of age or at least 28 days following the first dose.

Students at post-high school educational institutions

Students at post-high school educational institutions without evidence of measles immunity need two doses of MMR vaccine, with the second dose administered no earlier than 28 days after the first dose.

Adults

People who are born during or after 1957 who do not have evidence of immunity against measles should get at least one dose of MMR vaccine.

Postexposure Prophylaxis

People exposed to measles who cannot readily show that they have evidence of immunity against measles should be offered postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) or be excluded from the setting (school, hospital, childcare). To potentially provide protection or modify the clinical course of disease among susceptible persons, either administer MMR vaccine within 72 hours of initial measles exposure, or immunoglobulin (IG) within six days of exposure. Do not administer MMR vaccine and IG simultaneously, as this practice invalidates the vaccine.

MMR vaccine as postexposure prophylaxis

If MMR vaccine is not administered within 72 hours of exposure as PEP, MMR vaccine should still be offered at any interval following exposure to the disease in order to offer protection from future exposures. People who receive MMR vaccine or IG as PEP should be monitored for signs and symptoms consistent with measles for at least one incubation period.

If many measles cases are occurring among infants younger than 12 months of age, measles vaccination of infants as young as 6 months of age may be used as an outbreak control measure. Note that children vaccinated before their first birthday should be revaccinated when they are 12 through 15 months old and again when they are 4 through 6 years of age.

Except in healthcare settings, unvaccinated people who receive their first dose of MMR vaccine within 72 hours after exposure may return to childcare, school, or work.

Immunoglobulin (IG) as postexposure prophylaxis

People who are at risk for severe illness and complications from measles, such as infants younger than 12 months of age, pregnant women without evidence of measles immunity, and people with severely compromised immune systems, should receive IG. Intramuscular IG (IGIM) should be given to all infants younger than 12 months of age who have been exposed to measles. For infants aged 6 through 11 months, MMR vaccine can be given in place of IG, if administered within 72 hours of exposure. Because pregnant women might be at higher risk for severe measles and complications, intravenous IG (IGIV) should be administered to pregnant women without evidence of measles immunity who have been exposed to measles. People with severely compromised immune systems who are exposed to measles should receive IGIV regardless of immunologic or vaccination status because they might not be protected by MMR vaccine.

IG should not be used to control measles outbreaks, but rather to reduce the risk for infection and complications in the people receiving it. IGIM can be given to other people who do not have evidence of immunity against measles, but priority should be given to people exposed in settings with intense, prolonged, close contact, such as a household, daycare, or classroom where the risk of transmission is highest.

After receipt of IG, people cannot return to healthcare settings. In other settings, such as childcare, school, or work, factors such as immune status, intense or prolonged contact, and presence of populations at risk, should be taken into consideration before allowing people to return. These factors may decrease the effectiveness of IG or increase the risk of disease and complications depending on the setting to which they are returning.

The recommended dose of IGIM is 0.5 mL/kg of body weight (maximum dose = 15 mL) and the recommended dose of IGIV is 400 mg/kg.

Postexposure prophylaxis for healthcare personnel

If a healthcare provider without evidence of immunity is exposed to measles, MMR vaccine should be given within 72 hours, or IG should be given within 6 days when available. Exclude healthcare personnel without evidence of immunity from duty from day 5 after first exposure to day 21 after last exposure, regardless of postexposure vaccine.

Comments (0)